This course will investigate documentary films as social and political texts in order to identify historical and contemporary views on schools and the purpose(s) of education. The May X will examine primarily films addressing poverty, class, race, and privilege as they intersect with the purposes and realities of public education in the U.S.

Monday, May 30, 2016

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Sample Commentaries

Three of my commentaries from The State (Columbia, SC)

See Also

University of Georgia professor explains his ‘Asperger’s Advantage’ and disabling assumption of disorder

Peter Smagorinsky, University of Georgia

People considered “mentally ill” were, until recent generations, confined to institutions where they would be out of society’s sight and mind. As we have become more humane as a nation, and as understanding of human difference has helped to provide better life opportunities for those who are not considered “normal,” schools have enrolled far more students who once would not have been allowed inside their doors.

I have, in the last 20 years or so, taken a much greater interest in such people. In fact, I am among them, as are several people in my family. Various people in my gene pool have been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, Tourette’s syndrome, chronic anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive thinking, oppositional-defiance, and other conditions. I suspect that many readers can say the same.

I have written a good deal of late in academic journals about “neurodivergence,” the wide range of ways of being in the world produced by the neurological system. The issues are decidedly complex and have taken me years to begin to grasp, and I am still learning. In this essay I wish to discuss one thing about which I have become confident: the disabling notion of “disorder.”

UGA professor Peter Smagorinsky with doctoral advisee Stephanie Shelton at the May graduation.

When I listed syndromes and conditions earlier in this essay, I did not use the term “disorder.” Technically, these terms are often accompanied by either “disorder” or “disability,” as in Autism Spectrum Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and so on. I hope to persuade readers that using such phrasings serves to perpetuate the notion that being different from most people represents a form of disorder.

I’ll confine my attention here to a few conditions that are assumed to be, ever and always, disorders: ways of being that produce poor and threatening functioning in society. The Autism Society of America states that Asperger’s Disorder is synonymous with Asperger’s Syndrome. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is typically known as OCD; and Anxiety Disorder has its own Wikipedia entry.

In part because of the ways in which these conditions are named, people tend to believe that those who are made up in these ways have a stable, everlasting deficiency, perhaps even a chronic illness, from which they are inevitably said to “suffer.” I don’t wish to suggest that many people do not indeed suffer from conditions like depression, or that a severe bipolar makeup is just another okay way of being in the world. Although some of my colleagues in the neurodiversity movement would disagree, I can only conclude at this point in my understanding that extreme versions of these makeups can make social life so difficult that they are debilitating in and of themselves.

As one whose neurodivergence includes Asperger’s, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive thinking, however, I disagree with the general view that having this makeup makes me, and those like me, necessarily disordered at all times and in all places. If anything, Asperger’s is about as highly ordered a way of being as is possible. We are oriented to patterns, routines, and other aspects of living highly ordered, often predictable lives. Yet to many, such a life is one of disability and deficiency, and is for all such people in all situations.

I profoundly reject this judgment. As part of my rebellion against this stereotype, I have begun referring to my Asperger’s Advantage, especially when Asperger’s is bundled with my anxiety and obsessive-compulsive thinking. How can three disorders be considered an advantageous order?

First, these conditions are not always an advantage. In some situations, they are indeed disabling. I can’t fly without Xanax, and can’t give public talks without Inderal. I know I’m not alone; every airport I know of is teeming with bars that operate around the clock, with alcohol then freely available in flight; and public speaking is feared more than death itself.

In academia, however, this triad of conditions gives me the advantage that I claim. Researchers who can see patterns and go into meticulous detail without losing focus—traits of Asperger’s—tend to have successful careers in publish-or-perish environments. Those who are anxious are often incapable of leaving matters unfinished or hanging, leading to a disposition to finish tasks promptly and dependably. And obsessive-compulsiveness allows one to stick with a topic, sometimes when others would be more preferable, until a task is done.

As a package, this set of traits is hard to beat if your job security depends on publishing research, as a good part of mine is. The teaching aspect of academia might or might not benefit from such a makeup. Universities have employed many brilliant researchers who have had trouble communicating with students and colleagues, leading me to conclude that people like me will not always make good teachers.

In this sense, whether or not my conditions represent a disorder is entirely a matter of context. Disorder is relational and situational, not absolute and irrevocable, as terminology and everyday assumption suggest. The same makeup might be ideal, or disorder, depending on the environment. Even within one profession, university teaching, one might be considered successful in one area, research, and unsuccessful in another, teaching.

Personally, I’ve been teaching in high schools and universities for the last 40 years. I’ve gotten tenure in Midwestern schools based on my teaching, and tenure in universities based on my research. I don’t say that to boast, only to offer an example of how it’s possible to undertake a teaching life while also embodying neurodivergence.

Put me in a different setting and I might indeed be, if not disordered, at least dysfunctional. I would make a horrid politician, for instance. Beyond the problem of taking drugs constantly to make speeches, I could not engage in the endless pandering and gladhanding that seem required of the job. Asperger’s does not accommodate small talk or an emphasis on social conventions. In this context, I would be an utter failure.

My point here is both simple and complex: “Disorder” is an inappropriate term to attach as a fundamental part of the name of a neurological condition. Whether it’s order or disorder is a matter of how it works in relation to other people and settings. Unless this basic idea becomes better understood, too many people will go through life burdened by a false sense of who they are and what their potential is.

Thursday, May 26, 2016

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

How to Judge the Success of K-12 Education Policy

By Arthur H. Camins

As my morning train passed through the tunnel, a faster-moving train on a parallel track grabbed my attention as it passed on my left, going in the same direction. For a few moments, I experienced the discomfiting feeling that I had spontaneously reversed direction, moving away from, rather than toward, my final station. Reason told me that I was still headed to my destination, but I turned to my right and peered through the darkness at the stationary tunnel wall just to check. My sense of forward motion returned. Physicists explain this phenomenon as relative motion. Speed and direction are measured in relation to a reference point. Contrary to the adage, perception isn't always everything.

Stick with me. This is a metaphor for education policy and social justice.

In education, it is vital to remember frames of reference. We need to know about both faster- and slower-moving trains. We need to be clear about what we left behind, where we want to go, and with whom. We need to be cognizant of who is traveling on which track and not forget to take into account the complex education transport system.

An external observer of my morning train, or any passenger grounded in reality, would have known that relative to the departure point, both trains moved continuously forward.

So it is with education—with one big difference. External critics often ignore the fact that some trains have more powerful engines, ride on tracks with less friction, hold a larger supply of fuel, and carry different passengers. However, unlike physicists, policymakers often forget to consider frames of reference. They ignore a fundamental principle of science. Scientists use models to investigate and explain the natural world, but understand that models have limits. Designers of current education improvement, on the other hand, tend to focus blame on teachers and principals while ignoring other significant parts of the system. It is like blaming the drivers, conductors, and passengers for the speed and arrival time of the slower train.

—Getty

Many current education policymakers try to explain complex phenomena such as disparity in education outcomes with reference to only some parts of the system, such as teachers' or students' persistence. They ignore other contributing factors, such as unemployment, family and neighborhood stability, differential access to health care, and inequitable school funding. When they look exclusively at narrowly defined scores on standardized tests, everything seems like backward motion. When some critics of American education look at seemingly faster-moving school systems such as those in Finland or Ontario, they only notice speed and ignore how the systems are built and supported.

As is the case with prejudice-driven stereotypes, even some people inside school systems become so accustomed to looking at who is moving faster that they forget to recognize their own significant progress.

Children, classrooms, and schools all have an education destination. Some students get a head start because their parents have more time and financial resources. Some students get to ride on faster trains because they live in communities that can commit more resources to local schools. And notwithstanding the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, students' race remains a substantial determinant of which train children can get aboard. Different tracks are not just a metaphor for school resource variations. Teaching students on different tracks, also known as ability grouping, is still common within many schools.

"In education, it is vital to remember frames of reference."

Education in the United States is unequal by design. It is structured to perpetuate inequality and segregation. Some students continue to leave school better educated than others. This is not the de facto result of parental selection of schools or neighborhoods. Differential funding of schools through inequitable property taxes is a choice. Housing segregation is the result of deliberate policy decisions and zoning regulations. In-school tracking and differential instructional decisions are intentional choices, too. These longtime fixtures of our society appear to be givens, but that does not imply that they are not purposeful political choices. This makes them harder, but not impossible, to change.

However, let's not forget to consider frames of reference. If we occasionally turn away from the faster-moving train of inequality, there are sure signs of progress toward equity.

The first two promising developments are growing support for what was once considered unrealistic—passage of laws in an increasing number of cities setting a minimum wage of $15 an hour, and the burgeoning movement to opt out of high-stakes testing. The former means more money in workers' paychecks, which in turn leads to families that are less stressed and more stable and to more children who are ready to learn. The latter, if its growing influence is realized in different policy decisions, will mean more time for meaningful learning. Both suggest a shift in the perception of what is possible when average citizens get together to demand change. That's progress relative to where we have been.

A third sign of progress is the developing body of knowledge about effective teaching and learning, which has yet to be fully realized in daily instruction. For example, because we know that learning is an active process, the old practice of passive learning and rote memorization should fade away. Because we know that early development affects children's later learning, we should be investing in family health and well-being. Because we know that students' emotional health affects learning, we should invest in family and community stability and promote supportive classroom culture. Because we know that learning in diverse environments is good for all children, we should be promoting integrated classrooms, schools, and neighborhoods.

A battle is raging between two solutions to different education tracks. One is to give a few students an opportunity to jump aboard a theoretically faster-moving train with limited available space. That track symbolizes charter schools. However, on average, they are no more effective than the regular public schools from which they drain limited funds, and they are removed from the democratic control of communities.

The other solution is systemic, addressing not just the content and quality of instruction and school leadership, but also inequity in funding and the conditions of people's lives in communities through investment in jobs, universal preschool, health care, and access to higher education.

My perception of my morning train ride was constrained by the reference points in the tunnel. So it is if we confine our thinking to accepting the limits of the current education system and the inequity that surrounds us. Our new reference point for education should be ensuring what it takes to prepare every child to be successful in life, work, and citizenship.

Arthur H. Camins is the director of the Center for Innovation in Engineering and Science Education at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. He has taught and been an administrator in New York City; Hudson, Mass.; and Louisville, Ky. The ideas expressed in this essay are his alone and do not represent Stevens Institute.

Better Use of Information Could Help Agencies Identify Disparities and Address Racial Discrimination

Better Use of Information Could Help Agencies Identify Disparities and Address Racial Discrimination

The percentage of K-12 public schools in the United States with students who are poor and are mostly Black or Hispanic is growing and these schools share a number of challenging characteristics. From school years 2000-01 to 2013-14 (the most recent data available), the percentage of all K-12 public schools that had high percentages of poor and Black or Hispanic students grew from 9 to 16 percent, according to GAO’s analysis of data from the Department of Education (Education). These schools were the most racially and economically concentrated: 75 to 100 percent of the students were Black or Hispanic and eligible for free or reduced-price lunch—a commonly used indicator of poverty. GAO’s analysis of Education data also found that compared with other schools, these schools offered disproportionately fewer math, science, and college preparatory courses and had disproportionately higher rates of students who were held back in 9th grade, suspended, or expelled.

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Neil Gaiman - Inspirational Commencement Speech at the University of the Arts 2012

Neil Gaiman - Inspirational Commencement Speech at the University of the Arts 2012

134th Commencement

May 17, 2012

May 17, 2012

I never really expected to find myself giving advice to people graduating from an establishment of higher education. I never graduated from any such establishment. I never even started at one. I escaped from school as soon as I could, when the prospect of four more years of enforced learning before I'd become the writer I wanted to be was stifling.

I got out into the world, I wrote, and I became a better writer the more I wrote, and I wrote some more, and nobody ever seemed to mind that I was making it up as I went along, they just read what I wrote and they paid for it, or they didn't, and often they commissioned me to write something else for them.

Which has left me with a healthy respect and fondness for higher education that those of my friends and family, who attended Universities, were cured of long ago.

Looking back, I've had a remarkable ride. I'm not sure I can call it a career, because a career implies that I had some kind of career plan, and I never did. The nearest thing I had was a list I made when I was 15 of everything I wanted to do: to write an adult novel, a children's book, a comic, a movie, record an audiobook, write an episode ofDoctor Who... and so on. I didn't have a career. I just did the next thing on the list.

So I thought I'd tell you everything I wish I'd known starting out, and a few things that, looking back on it, I suppose that I did know. And that I would also give you the best piece of advice I'd ever got, which I completely failed to follow.

First of all: When you start out on a career in the arts you have no idea what you are doing.

This is great. People who know what they are doing know the rules, and know what is possible and impossible. You do not. And you should not. The rules on what is possible and impossible in the arts were made by people who had not tested the bounds of the possible by going beyond them. And you can.

If you don't know it's impossible it's easier to do. And because nobody's done it before, they haven't made up rules to stop anyone doing that again, yet.

Secondly, If you have an idea of what you want to make, what you were put here to do, then just go and do that.

And that's much harder than it sounds and, sometimes in the end, so much easier than you might imagine. Because normally, there are things you have to do before you can get to the place you want to be. I wanted to write comics and novels and stories and films, so I became a journalist, because journalists are allowed to ask questions, and to simply go and find out how the world works, and besides, to do those things I needed to write and to write well, and I was being paid to learn how to write economically, crisply, sometimes under adverse conditions, and on time.

Sometimes the way to do what you hope to do will be clear cut, and sometimes it will be almost impossible to decide whether or not you are doing the correct thing, because you'll have to balance your goals and hopes with feeding yourself, paying debts, finding work, settling for what you can get.

Something that worked for me was imagining that where I wanted to be – an author, primarily of fiction, making good books, making good comics and supporting myself through my words – was a mountain. A distant mountain. My goal.

And I knew that as long as I kept walking towards the mountain I would be all right. And when I truly was not sure what to do, I could stop, and think about whether it was taking me towards or away from the mountain. I said no to editorial jobs on magazines, proper jobs that would have paid proper money because I knew that, attractive though they were, for me they would have been walking away from the mountain. And if those job offers had come along earlier I might have taken them, because they still would have been closer to the mountain than I was at the time.

I learned to write by writing. I tended to do anything as long as it felt like an adventure, and to stop when it felt like work, which meant that life did not feel like work.

Thirdly, When you start off, you have to deal with the problems of failure. You need to be thickskinned, to learn that not every project will survive. A freelance life, a life in the arts, is sometimes like putting messages in bottles, on a desert island, and hoping that someone will find one of your bottles and open it and read it, and put something in a bottle that will wash its way back to you: appreciation, or a commission, or money, or love. And you have to accept that you may put out a hundred things for every bottle that winds up coming back.

The problems of failure are problems of discouragement, of hopelessness, of hunger. You want everything to happen and you want it now, and things go wrong. My first book – a piece of journalism I had done for the money, and which had already bought me an electric typewriter from the advance – should have been a bestseller. It should have paid me a lot of money. If the publisher hadn't gone into involuntary liquidation between the first print run selling out and the second printing, and before any royalties could be paid, it would have done.

And I shrugged, and I still had my electric typewriter and enough money to pay the rent for a couple of months, and I decided that I would do my best in future not to write books just for the money. If you didn't get the money, then you didn't have anything. If I did work I was proud of, and I didn't get the money, at least I'd have the work.

Every now and again, I forget that rule, and whenever I do, the universe kicks me hard and reminds me. I don't know that it's an issue for anybody but me, but it's true that nothing I did where the only reason for doing it was the money was ever worth it, except as bitter experience. Usually I didn't wind up getting the money, either. The things I did because I was excited, and wanted to see them exist in reality have never let me down, and I've never regretted the time I spent on any of them.

The problems of failure are hard.

The problems of success can be harder, because nobody warns you about them.

The first problem of any kind of even limited success is the unshakable conviction that you are getting away with something, and that any moment now they will discover you. It's Imposter Syndrome, something my wife Amanda christened the Fraud Police.

In my case, I was convinced that there would be a knock on the door, and a man with a clipboard (I don't know why he carried a clipboard, in my head, but he did) would be there, to tell me it was all over, and they had caught up with me, and now I would have to go and get a real job, one that didn't consist of making things up and writing them down, and reading books I wanted to read. And then I would go away quietly and get the kind of job where you don't have to make things up any more.

The problems of success. They're real, and with luck you'll experience them. The point where you stop saying yes to everything, because now the bottles you threw in the ocean are all coming back, and have to learn to say no.

I watched my peers, and my friends, and the ones who were older than me and watch how miserable some of them were: I'd listen to them telling me that they couldn't envisage a world where they did what they had always wanted to do any more, because now they had to earn a certain amount every month just to keep where they were. They couldn't go and do the things that mattered, and that they had really wanted to do; and that seemed as a big a tragedy as any problem of failure.

And after that, the biggest problem of success is that the world conspires to stop you doing the thing that you do, because you are successful. There was a day when I looked up and realised that I had become someone who professionally replied to email, and who wrote as a hobby. I started answering fewer emails, and was relieved to find I was writing much more.

Fourthly, I hope you'll make mistakes. If you're making mistakes, it means you're out there doing something. And the mistakes in themselves can be useful. I once misspelled Caroline, in a letter, transposing the A and the O, and I thought, “Coralinelooks like a real name...”

And remember that whatever discipline you are in, whether you are a musician or a photographer, a fine artist or a cartoonist, a writer, a dancer, a designer, whatever you do you have one thing that's unique. You have the ability to make art.

And for me, and for so many of the people I have known, that's been a lifesaver. The ultimate lifesaver. It gets you through good times and it gets you through the other ones.

Life is sometimes hard. Things go wrong, in life and in love and in business and in friendship and in health and in all the other ways that life can go wrong. And when things get tough, this is what you should do.

Make good art.

I'm serious. Husband runs off with a politician? Make good art. Leg crushed and then eaten by mutated boa constrictor? Make good art. IRS on your trail? Make good art. Cat exploded? Make good art. Somebody on the Internet thinks what you do is stupid or evil or it's all been done before? Make good art. Probably things will work out somehow, and eventually time will take the sting away, but that doesn't matter. Do what only you do best. Make good art.

Make it on the good days too.

And Fifthly, while you are at it, make your art. Do the stuff that only you can do.

The urge, starting out, is to copy. And that's not a bad thing. Most of us only find our own voices after we've sounded like a lot of other people. But the one thing that you have that nobody else has is you. Your voice, your mind, your story, your vision. So write and draw and build and play and dance and live as only you can.

The moment that you feel that, just possibly, you're walking down the street naked, exposing too much of your heart and your mind and what exists on the inside, showing too much of yourself. That's the moment you may be starting to get it right.

The things I've done that worked the best were the things I was the least certain about, the stories where I was sure they would either work, or more likely be the kinds of embarrassing failures people would gather together and talk about until the end of time. They always had that in common: looking back at them, people explain why they were inevitable successes. While I was doing them, I had no idea.

I still don't. And where would be the fun in making something you knew was going to work?

And sometimes the things I did really didn't work. There are stories of mine that have never been reprinted. Some of them never even left the house. But I learned as much from them as I did from the things that worked.

Sixthly. I will pass on some secret freelancer knowledge. Secret knowledge is always good. And it is useful for anyone who ever plans to create art for other people, to enter a freelance world of any kind. I learned it in comics, but it applies to other fields too. And it's this:

People get hired because, somehow, they get hired. In my case I did something which these days would be easy to check, and would get me into trouble, and when I started out, in those pre-internet days, seemed like a sensible career strategy: when I was asked by editors who I'd worked for, I lied. I listed a handful of magazines that sounded likely, and I sounded confident, and I got jobs. I then made it a point of honour to have written something for each of the magazines I'd listed to get that first job, so that I hadn't actually lied, I'd just been chronologically challenged... You get work however you get work.

People keep working, in a freelance world, and more and more of today's world is freelance, because their work is good, and because they are easy to get along with, and because they deliver the work on time. And you don't even need all three. Two out of three is fine. People will tolerate how unpleasant you are if your work is good and you deliver it on time. They'll forgive the lateness of the work if it's good, and if they like you. And you don't have to be as good as the others if you're on time and it's always a pleasure to hear from you.

When I agreed to give this address, I started trying to think what the best advice I'd been given over the years was.

And it came from Stephen King twenty years ago, at the height of the success of Sandman. I was writing a comic that people loved and were taking seriously. King had liked Sandman and my novel with Terry Pratchett, Good Omens, and he saw the madness, the long signing lines, all that, and his advice was this:

“This is really great. You should enjoy it.”

And I didn't. Best advice I got that I ignored.Instead I worried about it. I worried about the next deadline, the next idea, the next story. There wasn't a moment for the next fourteen or fifteen years that I wasn't writing something in my head, or wondering about it. And I didn't stop and look around and go, this is really fun. I wish I'd enjoyed it more. It's been an amazing ride. But there were parts of the ride I missed, because I was too worried about things going wrong, about what came next, to enjoy the bit I was on.

That was the hardest lesson for me, I think: to let go and enjoy the ride, because the ride takes you to some remarkable and unexpected places.

And here, on this platform, today, is one of those places. (I am enjoying myself immensely.)

To all today's graduates: I wish you luck. Luck is useful. Often you will discover that the harder you work, and the more wisely you work, the luckier you get. But there is luck, and it helps.

We're in a transitional world right now, if you're in any kind of artistic field, because the nature of distribution is changing, the models by which creators got their work out into the world, and got to keep a roof over their heads and buy sandwiches while they did that, are all changing. I've talked to people at the top of the food chain in publishing, in bookselling, in all those areas, and nobody knows what the landscape will look like two years from now, let alone a decade away. The distribution channels that people had built over the last century or so are in flux for print, for visual artists, for musicians, for creative people of all kinds.

Which is, on the one hand, intimidating, and on the other, immensely liberating. The rules, the assumptions, the now-we're supposed to's of how you get your work seen, and what you do then, are breaking down. The gatekeepers are leaving their gates. You can be as creative as you need to be to get your work seen. YouTube and the web (and whatever comes after YouTube and the web) can give you more people watching than television ever did. The old rules are crumbling and nobody knows what the new rules are.

So make up your own rules.

Someone asked me recently how to do something she thought was going to be difficult, in this case recording an audio book, and I suggested she pretend that she was someone who could do it. Not pretend to do it, but pretend she was someone who could. She put up a notice to this effect on the studio wall, and she said it helped.

So be wise, because the world needs more wisdom, and if you cannot be wise, pretend to be someone who is wise, and then just behave like they would.

And now go, and make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here. Make good art.

Friday, May 20, 2016

Thursday, May 19, 2016

The Trouble with the ‘Culture of Poverty’ and Other Stereotypes about People in Poverty by Paul C. Gorski

The Trouble with the ‘Culture of Poverty’ and Other Stereotypes about People in Poverty by Paul C. Gorski

Stereotype 1: Poor People Do Not Value Education

The most popular measure of parental attitudes about education, particularly among teachers, is “family involvement” (Jeynes, 2011). This stands to reason, as research consistently confirms a correlation between family involvement and school achievement (Lee & Bowen, 2006; Oyserman, Brickman, & Rhodes, 2007). However, too often, our notions of family involvement are limited in scope, focused only on in-school involvement—the kind of involvement that requires parents and guardians to visit their children’s schools or classrooms. While it is true that low-income parents and guardians are less likely to participate in this brand of “involvement” (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2005), they engage in home-based involvement strategies, such as encouraging children to read and limiting television watching, more frequently than their wealthier counterparts (Lee & Bowen, 2006).

It might be easy, given the stereotype that low-income families do not value education, to associate low-income families’ less consistent engagement in on-site, publicly visible, school involvement, such as parent-teacher conferences, with an ethic that devalues education. In fact, research has shown that many teachers assume that low-income families are completely uninvolved in their children’s education (Patterson, Hale, & Stessman, 2007). However, in order to assume a direct relationship between disparities in on-site involvement and a disregard for the importance of school, we would have to omit considerable amounts of contrary evidence. First, low-income parents and guardians experience significant class-specific barriers to school involvement. These include consequences associated with the scarcity of living wage jobs, such as the ability to afford childcare or public transportation or the ability to afford to take time off from wage work (Bower & Griffin, 2011; Li, 2010). They also include the weight of low-income parents’ and guardians’ own school experiences, which often were hostile and unwelcoming (Lee & Bowen, 2006). Although some schools and districts have responded to these challenges by providing on-site childcare, transportation, and other mitigations, the fact remains that, on average, this type of involvement is considerably less accessible to poor families than to wealthier ones.

Broadly speaking, there simply is no evidence, beyond differences in on-site involvement, that attitudes about the value of education in poor communities differ in any substantial way from those in wealthier communities. The evidence, in fact, suggests that attitudes about the value of education among families in poverty are identical to those among families in other socioeconomic strata. In other words, poor people, demonstrating impressive resilience, value education just as much as wealthy people (Compton-Lilly, 2003; Grenfell & James, 1998) despite the fact that they often experience schools as unwelcoming and inequitable.

For example:

- in a study of low-income urban families, Compton-Lilly (2000) found that parents overwhelmingly have high educational expectations for their children and expect their children’s teachers to have equally high expectations for them, particularly in reading;

- in their study focusing on low-income African American parents, Cirecie West-Olatunji and her colleagues (2010) found that they regularly reached out to their children’s schools and stressed the importance of education to their children;

- similarly, Patricia Jennings (2004), in her study on how women on welfare respond to the “culture of poverty” stereotype, found that single mothers voraciously valued and sought out educational opportunities for themselves, both as a way to secure living wage work and as an opportunity to model the importance of school to their children;

- based on their study of 234 low-income parents and guardians, Kathryn Drummond and Deborah Stipek (2004) found that they worked tirelessly to support their children’s intellectual development;

- during an ethnographic study of a racially diverse group of low-income families, Guofang Li (2010) found that parents, including those who were not English-proficient, used a variety of strategies to bolster their children’s literacy development;

- a recent study shows, contrasting popular perception, that poor families invest just as much time as their wealthier counterparts exploring school options for their children (Grady, Bielick, & Aud, 2010); and

- using data from the more than 20,000 families that participated in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Carey Cooper and her colleagues (2010) found, quite simply, that “poor parents reported engaging their children in home-learning activities as often as nonpoor parents” (p. 876).

As with any stereotype, the notion that people in poverty don’t value education might have more to do with our well-intended misinterpretations of social realities than with theirdisinterest in school. For example, some low-income families, and particularly low-income immigrant families, may not be as informed as their wealthier counterparts about how educational systems in the U.S. work (Ceja, 2006; Lareau & Meininger, 2008), an obvious consequence of the alienation from school systems many poor people experience, starting with their time as students. It can be easy to interpret this lack of understanding, which is a symptom, itself, of educational inequities, as disinterest. Similarly, it can be easy to interpret lower levels of some types of school involvement, including types that are not scheduled or structured to be accessible to low-income families, as evidence that low-income parents simply don’t care about school. But these interpretations, in the end, are based more on stereotype than reality. They are, for the most part, just plain wrong.

The challenge for us, then, is to do the difficult work of considering what we are apt to misinterpret, not simply as a fluffy attempt at “inclusion,” but as a high-stakes matter of student success. After all, research also shows that when teachers perceive that their parents value education, they tend to assess student work more positively (Hill & Craft, 2003). Bias matters.

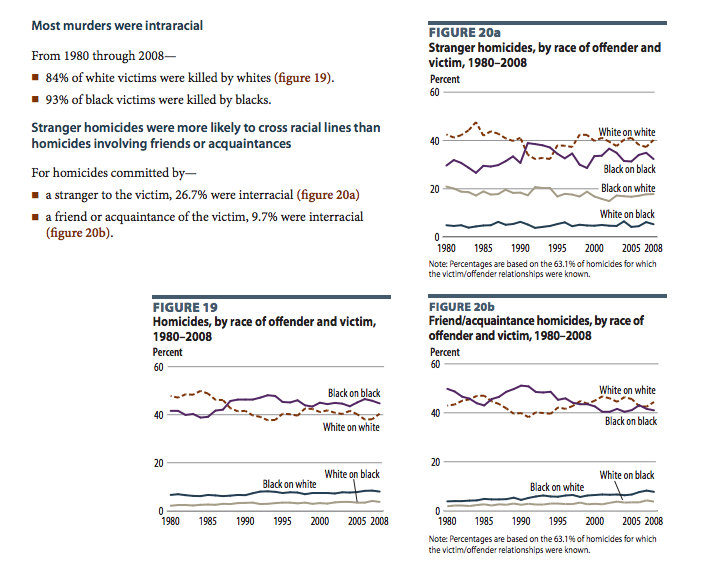

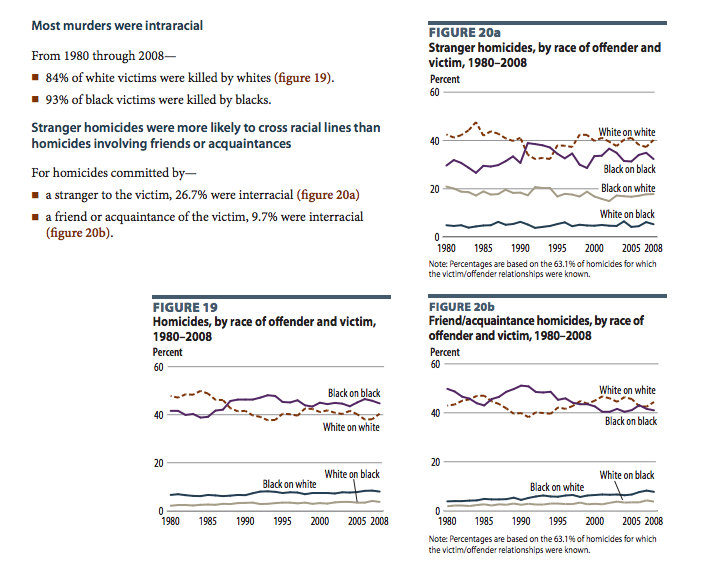

Most Murders Are within Same Race

Like "thug" and "disruptive students," a much more racially charged and racist refrain is "black on black" crime.

The phrase includes race and is factual—although fatally incomplete.

As well, many of the most credible and critical voices confronting racism are apt to concede the looming problem of blacks killing blacks—such as Ta-Nehisi Coates arguing that "[w]hen policing is delegitimized, when it becomes an occupying force, the community suffers":

Crime and homicides are the result of familiarity and proximity. Our families, our social circles, our neighborhoods, and our communities are far more dangerous to each of us than any stranger or any unfamiliar territory. And as long as familiarity and proximity remain mostly segregated, our crimes and murders are likely to remain within the same race.

To utter "black on black" crime in order to claim a causal relationship between race and crime is dishonest. Race in crime is a marker, not a cause agent, especially not a cause agent unique to any race.

The phrase includes race and is factual—although fatally incomplete.

As well, many of the most credible and critical voices confronting racism are apt to concede the looming problem of blacks killing blacks—such as Ta-Nehisi Coates arguing that "[w]hen policing is delegitimized, when it becomes an occupying force, the community suffers":

It will not do to note that 99 percent of the time the police mediate conflicts without killing people anymore than it will do for a restaurant to note that 99 percent of the time rats don’t run through the dining room. Nor will it do to point out that most black citizens are killed by other black citizens [emphasis added], not police officers, anymore than it will do to point out that most American citizens are killed by other American citizens, not terrorists. If officers cannot be expected to act any better than ordinary citizens, why call them in the first place? Why invest them with any more power?The issue is not the fact of black on black crime, but that crime and homicide are overwhelmingly within race:

U.S. Department of Justice: Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008 (November 2011).

Crime and homicides are the result of familiarity and proximity. Our families, our social circles, our neighborhoods, and our communities are far more dangerous to each of us than any stranger or any unfamiliar territory. And as long as familiarity and proximity remain mostly segregated, our crimes and murders are likely to remain within the same race.

To utter "black on black" crime in order to claim a causal relationship between race and crime is dishonest. Race in crime is a marker, not a cause agent, especially not a cause agent unique to any race.

Wednesday, May 18, 2016

Corporal punishment

University study finds spanking harmful for children, Desiree Chew

The Stream: Should parents spare the spank

Here’s What Getting Spanked as a Kid Did to Your Personality, According to Science, Jordyn Taylor

Risks of Harm from Spanking Confirmed by Analysis of Five Decades of Research

Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses, Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Grogan-Kaylor, Andrew

Follow Dr. Stacey Patton on Twitter and Facebook; and see Spare the Kids.

The Stream: Should parents spare the spank

Risks of Harm from Spanking Confirmed by Analysis of Five Decades of Research

Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses, Gershoff, Elizabeth T.; Grogan-Kaylor, Andrew

DOES CAUSALLY RELEVANT RESEARCH SUPPORT A BLANKET INJUNCTIONAGAINST DISCIPLINARY SPANKING BY PARENTS?

Diana Baumrind

I will use the term “spanking” (See Friedman and Schonberg [1996, p.853], and Strassberg and colleagues do [1994, p.446].) to refer to striking the child on the buttocks or extremities with an open hand without inflicting physical injury with the intention to modify behavior. Spanking is intended to be aversive, but not necessarily by inflicting physical pain.

---

Is Corporal Punishment an Effective Means of Discipline?

Corporal punishment leads to more immediate compliant behavior in children, but is also associated with physical abuse. Should parents be counseled for or against spanking?

Corporal Punishment Articles

- Corporal Punishment by Parents and Associated Child Behaviors and Experiences: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review (PDF, 879KB)

- Corporal Punishment, Physical Abuse, and the Burden of Proof: Reply to Baumrind, Larzelere, and Cowan (2002), Holden (2002), and Parke (2002) (PDF, 465KB)

- Ordinary Physical Punishment: Is It Harmful? Comment on Gershoff (2002) (PDF, 108KB)

- Perspectives on the Effects of Corporal Punishment: Comment on Gershoff (2002) (PDF, 96KB)

- Punishment Revisited-Science, Values, and the Right Question: Comment on Gershoff (2002)(PDF, 79KB)

WASHINGTON — Corporal punishment remains a widely used discipline technique in most American families, but it has also been a subject of controversy within the child development and psychological communities. In a large-scale meta-analysis of 88 studies, psychologist Elizabeth Thompson Gershoff, PhD, of the National Center for Children in Poverty at Columbia University, looked at both positive and negative behaviors in children that were associated with corporal punishment. Her research and commentaries on her work are published in the July issue of Psychological Bulletin, published by the American Psychological Association.

While conducting the meta-analysis, which included 62 years of collected data, Gershoff looked for associations between parental use of corporal punishment and 11 child behaviors and experiences, including several in childhood (immediate compliance, moral internalization, quality of relationship with parent, and physical abuse from that parent), three in both childhood and adulthood (mental health, aggression, and criminal or antisocial behavior) and one in adulthood alone (abuse of own children or spouse).

Gershoff found "strong associations" between corporal punishment and all eleven child behaviors and experiences. Ten of the associations were negative such as with increased child aggression and antisocial behavior. The single desirable association was between corporal punishment and increased immediate compliance on the part of the child.

The two largest effect sizes (strongest associations) were immediate compliance by the child and physical abuse of the child by the parent. Gershoff believes that these two strongest associations model the complexity of the debate around corporal punishment.

"That these two disparate constructs should show the strongest links to corporal punishment underlines the controversy over this practice. There is general consensus that corporal punishment is effective in getting children to comply immediately while at the same time there is caution from child abuse researchers that corporal punishment by its nature can escalate into physical maltreatment," Gershoff writes.

But, Gershoff also cautions that her findings do not imply that all children who experience corporal punishment turn out to be aggressive or delinquent. A variety of situational factors, such as the parent/child relationship, can moderate the effects of corporal punishment. Furthermore, studying the true effects of corporal punishment requires drawing a boundary line between punishment and abuse. This is a difficult thing to do, especially when relying on parents' self-reports of their discipline tactics and interpretations of normative punishment.

"The act of corporal punishment itself is different across parents - parents vary in how frequently they use it, how forcefully they administer it, how emotionally aroused they are when they do it, and whether they combine it with other techniques. Each of these qualities of corporal punishment can determine which child-mediated processes are activated, and, in turn, which outcomes may be realized," Gershoff concludes.

The meta-analysis also demonstrates that the frequency and severity of the corporal punishment matters. The more often or more harshly a child was hit, the more likely they are to be aggressive or to have mental health problems.

While the nature of the analyses prohibits causally linking corporal punishment with the child behaviors, Gershoff also summarizes a large body of literature on parenting that suggests why corporal punishment may actually cause negative outcomes for children. For one, corporal punishment on its own does not teach children right from wrong. Secondly, although it makes children afraid to disobey when parents are present, when parents are not present to administer the punishment those same children will misbehave.

In commentary published along with the Gershoff study, George W. Holden, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin, writes that Gershoff's findings "reflect the growing body of evidence indicating that corporal punishment does no good and may even cause harm." Holden submits that the psychological community should not be advocating spanking as a discipline tool for parents.

In a reply to Gershoff, researchers Diana Baumrind, PhD (Univ. of CA at Berkeley), Robert E. Larzelere, PhD (Nebraska Medical Center), and Philip Cowan, PhD (Univ.of CA at Berkeley), write that because the original studies in Gershoff's meta-analysis included episodes of extreme and excessive physical punishment, her finding is not an evaluation of normative corporal punishment.

"The evidence presented in the meta-analysis does not justify a blanket injunction against mild to moderate disciplinary spanking," conclude Baumrind and her team. Baumrind et al. also conclude that "a high association between corporal punishment and physical abuse is not evidence that mild or moderate corporal punishment increases the risk of abuse."

Baumrind et al. suggest that those parents whose emotional make-up may cause them to cross the line between appropriate corporal punishment and physical abuse should be counseled not to use corporal punishment as a technique to discipline their children. But, that other parents could use mild to moderate corporal punishment effectively. "The fact that some parents punish excessively and unwisely is not an argument, however, for counseling all parents not to punish at all."

In her reply to Baumrind et al., Gershoff states that excessive corporal punishment is more likely to be underreported than overreported and that the possibility of negative effects on children caution against the use of corporal punishment.

"Until researchers, clinicians, and parents can definitively demonstrate the presence of positive effects of corporal punishment, including effectiveness in halting future misbehavior, not just the absence of negative effects, we as psychologists can not responsibly recommend its use," Gershoff writes.

Lead authors can be reached at:

Elizabeth Gershoff

University office: (212) 304-7149

Home office: (212) 316-0387

Elizabeth Gershoff

University office: (212) 304-7149

Home office: (212) 316-0387

The American Psychological Association (APA), in Washington, DC, is the largest scientific and professional organization representing psychology in the United States and is the world's largest association of psychologists. APA's membership includes more than 155,000 researchers, educators, clinicians, consultants and students. Through its divisions in 53 subfields of psychology and affiliations with 60 state, territorial and Canadian provincial associations, APA works to advance psychology as a science, as a profession and as a means of promoting human welfare.

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

Monday, May 16, 2016

Sunday, May 15, 2016

Friday, May 13, 2016

Thursday, May 12, 2016

S.C. Supreme Court Rules For Poor, Rural Districts in Equity Lawsuit

S.C. Supreme Court Rules For Poor, Rural Districts in Equity Lawsuit

By Denisa R. Superville on November 13, 2014 12:14 PM

A 21-year-old legal battle waged by more than two dozen school districts that accused the state of South Carolina of failing to provide a "minimally adequate" education for poor and rural students came to an end Wednesday, after the state Supreme Court ruled in the districts' favor.

In a 3-2 ruling, the state high court upheld an earlier Circuit Court decision that said South Carolina officials failed to live up to their constitutional obligation to adequately fund poor and rural schools. The state's failure to address the "effects of pervasive poverty on students within the plaintiffs' school districts prevented those students from receiving the required opportunity," the ruling said.

But Chief Justice Jean Toal, who wrote the majority opinion, did not absolve the plaintiff districts for their role in exacerbating funding inequities, arguing that local spending priorities—for athletic facilities and other auxiliary services while students languished in "crumbling schools and toxic academic environments"—were also part of the problem.

However, the brunt of the responsibility was put on the defendants, among them the state of South Carolina, Gov. Nikki Haley, and the top two leaders in the state legislature.

The defendants "bear the burden articulated by our State's Constitution, and have failed in their constitutional duty to ensure that students in the Plaintiff Districts receive the requisite educational opportunity," the judge wrote. "Thousands of South Carolina's school children—the quintessential future of our state—have been denied this opportunity due to no more than historical accident."

The defendants argued that part of the districts' case was moot because the state funding formula for public schools has been revised several times since the lawsuit was filed and more money had been directed to early-childhood education. They also argued some students in the plaintiff districts had succeeded—evidence, they said, that there were opportunities for children to excel. The justices in the majority rejected those arguments.

The ruling directed both sides to come up with a solution and compelled both to design a plan that addresses the constitutional violation.

The two dissenting justices argued that school funding was a matter for the state legislature and that the court was overstepping its bounds.

The lawsuit has a long and complicated history. Since it was first filed in 1993, thousands of children have attended and graduated from schools in the plaintiff districts.

Abbeville County School District, et. al. v. the State of South Carolina was first filed on behalf of nearly 30 districts that alleged that the 1977 K-12 funding formula, which the legislature used to disburse school aid, was unfair to rural and poor areas.

The state successfully sought dismissal of the case in 1996, which the districts appealed. In 1999, the state Supreme Court ruled that the General Assembly was required by the state's constitution to "provide the opportunity for each child to receive a minimally adequate" public education, and sent the case back to the Circuit Court.

In a 2005 ruling, both sides had some measures of victory. Circuit Judge Thomas Cooper ordered the legislature to pour more money into early-childhood education, while the districts lost on issues related to teacher pay and buildings. Both sides appealed the portions of the case they lost, according to the Associated Press.

District supporters told local media that Wednesday's ruling was a long time coming and praised the South Carolina Supreme Court for acting in their favor. A former state superintendent called the funding mechanism a "premeditated felony" that should have long been remedied.

"Our state has given children in the most impoverished and rural portions of our state a chance of life," said Carl Epps, an attorney for the districts, told the Associated Press. "We look forward to working with the state so these children will indeed have the opportunities that a generation of poverty and lack of consistent state approach to education has caused."

Gov. Haley, who noted that she attended rural schools, said in a statement that she understood the challenges they faced and that she remained committed to public education.

The South Carolina decision has broad implications for the future of public school education funding in the state. Similar challenges to state funding mechanisms are underway in various states, including in Mississippi and Pennsylvania. Education advocates there are in process of seeking redress to rectify what they see as structural funding deficits that deny public school students of the education required either by those states' laws or constitutions.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)